How evolution drives success in the digital era

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/Think_Act_Magazine_Darwinism_Cover_EN_download_preview.jpg)

Change. Survive. Thrive. What your company needs to know to prosper in the digital age.

He's wound down countless startups and been dubbed Dr. Death along the way, but for Martin Pichinson and his observers, the failed venture-backed companies under his care offer a valuable opportunity: a chance to pick up the pieces and keep on innovating.

When it comes to technology startups in distress, death takes them all – from the highfliers to those that were just stumbling along. Look at Jawbone, designer of sleek portable speakers and wearable fitness trackers. It raised more than $1 billion over its life and had a valuation of more than $3 billion but, alas, ceased operations in the summer of 2017. Or Pebble Technology Corp., a trailblazer in the smartwatch space that collected a record $30.6 million through two crowdfunding campaigns only to be shut down and have its remains acquired by competitor Fitbit.

Then there’s Beepi, a Silicon Valley-based online marketplace for used cars that burned through $150 million in venture capital before winding down in early 2017. Or TellTale Games, which turned TV hits such as Game of Thrones into popular online games. It ran through a total of $54 million before using up its last life and shuttering operations in 2018. And finally, how about Theranos, a much-hyped diagnostics company that amassed a war chest of $1.4 billion until its false claims for a novel blood test blew up, leading to disgrace, lawsuits and one more tombstone in Silicon Valley’s graveyard of failed dreams.

What these failures share with hundreds of other startups that met a more discrete demise is their final caretaker. Martin Pichinson, a septuagenarian former music manager, runs probably the biggest operation for winding down failed companies in the Valley. For close to three decades, his firm Sherwood Partners has refined the process of taking over startups that are near death and selling off their physical and intangible assets to satisfy their creditors. With all the breathless reporting about mega-exits and serial entrepreneurs who strike it rich, the expeditious and efficient disposal of Silicon Valley's dead rarely gets any attention beyond homilies on failure in general. "It's a golden rule of the tech world," Pichinson explains at his offices in Los Angeles. "If you have 2,000 to 2,500 new companies hitting the market every year, there is no way they can all be successful. And the ones who don’t make it are not failures, they just didn't make it to the finish line. We are like the waste management of the industry," he says, part pained, part proud. "We are brought in to clean up, to salvage what's valuable so all parties can move on and focus on new things."

Pichinson bristles at the moniker that some in the industry have given him since the lethal dotcom crash of 2001 made him a household name: Dr. Death. He prefers to compare his services to a physician who brings bad news or a warden of an orphanage who tries to find new parents for ideas. In that sense, he defines one man's failure as another man's opportunity to get assets on the cheap and carry on innovating. "Every new segment in tech has companies that will not make it. Take the rush in spaceship companies. I am sure we will close down one or two of those."

A handful of calls come in every week seeking help from Sherwood to wind down companies after they've failed to raise new funds. Pichinson says he signs two to three deals each week that are either purely fee-based or take a cut from any intellectual property (IP) sold to the highest bidder. The latter category has been growing steadily as the hardware and furniture a dead startup leaves behind aren't worth much anymore. Pichinson focuses on slicing and dicing leftover patents and other intangibles through a second firm called agencyIP. That can be a bundle of patents or a single software module that a larger company wants to integrate into its existing service stack. "Today, a server is worth as much as a boat anchor. The real value is in IP," Pichinson explains.

Experts call what Sherwood specializes in ABC, a handy little acronym that stands for "assignment for the benefit of creditors." It's different from a traditional bankruptcy process as it can prevent such a filing and therefore be quicker and also force fewer company secrets into the open. Therefore a whole industry has evolved to handle last-minute loans and liquidations when all is lost. Companies such as Sherwood, Gerbsman Partners or Western Technology Investment are a natural flipside to the glorious image of Silicon Valley.

"We are like the waste management of the industry."

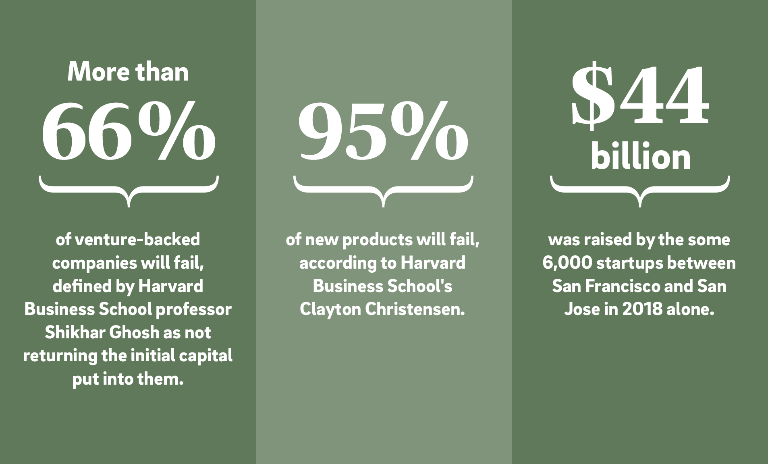

Between San Francisco and San Jose, at any given moment an estimated 6,000 startups are busy trying to come up with the next big thing. For that, they raised almost $44 billion last year alone and another $9.2 billion in the first quarter of 2019, according to CB Insights. When those funds are used up and investors are unwilling to front more money, Sherwood recoups what can be recouped. "We are an extension of the venture capital and venture debt world when they have decided they won’t get the returns they need," Pichinson says.

That kind of unseemly exit is more common than the industry lets on. Harvard Business School professor Shikhar Ghosh has been crunching the numbers of the tech ecosystem for years. Analyzing about 13,000 venture-backed companies going back two decades, he estimates that at least two-thirds of them are failures, not returning the initial capital put into them."VCs like to bury their dead very quietly. While something might be great for a small market with a nice $5 million business, venture capitalists don't want that. They want $5 billion," he explains. The herd of startups that VC firms bet on in their portfolios therefore needs to be culled fast to identify the few with the potential for a big exit. "Most companies should not exist," Ghosh says, defending the approach. If you do it quickly, it's not a bad outcome for everybody."

Sherwood has developed a well-oiled system over the years. After the call comes in, it takes about a week to compile a rough overview of assets and liabilities, followed by a timeline and budget for liquidation. Hardware auctions are outsourced, while the intangible assets are shopped around to a growing database of about 16,000 people in tech. Pichinson, in the meantime, sets up a temporary shell company to safeguard the remains, even taking over the domain name of a dead dotcom. "It pays to keep the lights on, pay the engineers and cloud services, keep filings up to date in order to have something marketable," he explains. Some IP might not find a new home, sitting on his shelves for a year. It will eventually be buried like the many other documents from the defunct company.

It may sound like most if not all items of value are recycled and repurposed under this system, but tell that to the entrepreneurs and founders in the trenches, and many beg to differ. They say the continuous die-offs create a lot of personal hurt and turmoil. Like this unnamed Valley veteran who started his own companies and has been brought in a few times to help find a buyer for a stalled startup or to prepare it for liquidation. He wants to stay in business and not rankle partners, so has withheld his name for this article. "If you are one of 20 companies in a portfolio that gets funding and this is your first time in the game, you don't realize that you're marked for death until it’s too late – when investors avoid discussions about the next round or stop returning your calls."

He admits that selling a struggling company to a competitor that wants the team, or wants to bury their product before it becomes a threat, can save it some assets and yield money to repay investors or creditors. But it leaves staff and founders empty-handed because the liquidation preferences are stacked against them. "This system creates tons and tons of waste if you measure the vitality of a business by whether it can get to an aggressive valuation in a timeframe that may not align with the realities of the market," he says.

What happens to the remains of a business once the fancy desks and other hardware have been dumped and once other companies have acquired IP from Sherwood? They become a largely overlooked archive of Silicon Valley failures – picture a warehouse filled with document boxes up to the ceiling. Since Pichinson and other liquidators are legally required to keep pertinent records for seven years, his company is sitting on a mountain of papers and electronic records that economists and historians consider quite valuable. "We pay lip service to failures, but we haven't really done much learning from failure at the organizational level," says David Kirsch, a business professor at the University of Maryland. That's why he's collaborated with Sherwood for the past eight years to save as many records as possible. Once a year, he would select a small fraction of Sherwood's haul and truck the pallets to the Hagley Center for the History of Business, Technology, and Society at the University of Delaware.

The goal is to preserve at least some records of the rich business history of Silicon Valley in the early 21st century. "Marty [Pichinson] has a unique window into the venture ecosystem that even top VCs don’t have since they always look forward to the next deal. He's the undertaker, and corpses tell a story, too. A corporation is like a social corpse that we can study," Kirsch says. The collection has so far only released the digital remains of a single company that folded in 2006. Any researcher can access its one million emails or tens of thousands of other documents, but the company's real name has been masked. In the next year or two, Kirsch wants to open up another five company records, and eventually aims for many more. "If we get to 50 companies, we'd have something really valuable. We could use machine learning and other methods to identify the leading indicators of failure, perhaps the burn rate, structural features, communication patterns and types of market tests."

Arthur Daemmrich, the director of Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., has also been in touch with the liquidator to gain a new perspective on the circle of innovation. "Most stories about innovation we tell our children are success stories, but we know 90% never make it to market," says Daemmrich. Sherwood’s dataset could help correct that popular misperception, he thinks. "Such an archive would be of tremendous value 50 years from now when we write about the era. Every university nowadays has a school of entrepreneurship and a startup hub," Daemmrich says. "That won't last forever, and we don’t know what comes next." One thing will keep happening, however: death by attrition, with undertakers like Pichinson ready to shovel reusable assets back into the maws of Silicon Valley's machine.

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/Think_Act_Magazine_Darwinism_Cover_EN_download_preview.jpg)

Change. Survive. Thrive. What your company needs to know to prosper in the digital age.

Curious about the contents of our newest Think:Act magazine? Receive your very own copy by signing up now! Subscribe here to receive our Think:Act magazine and the latest news from Roland Berger.