Roland Berger´s Clean Hydrogen Radar will analyze and explain upstream, midstream and downstream developments in all key global markets.

Cost improvements in renewables

The beginning of the end, or just the end of the beginning?

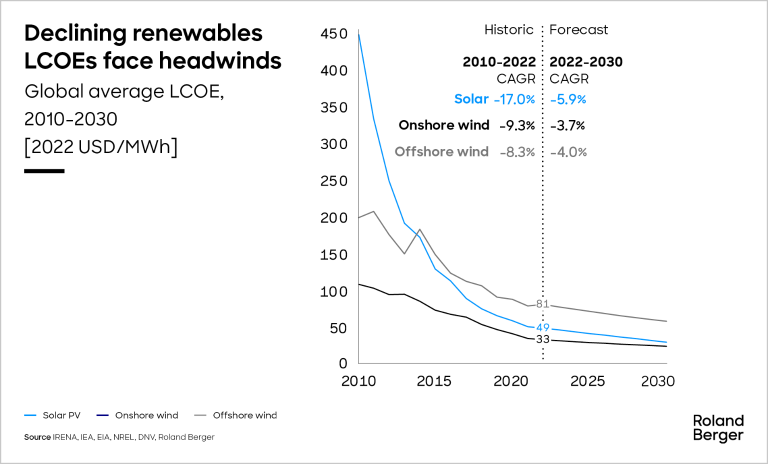

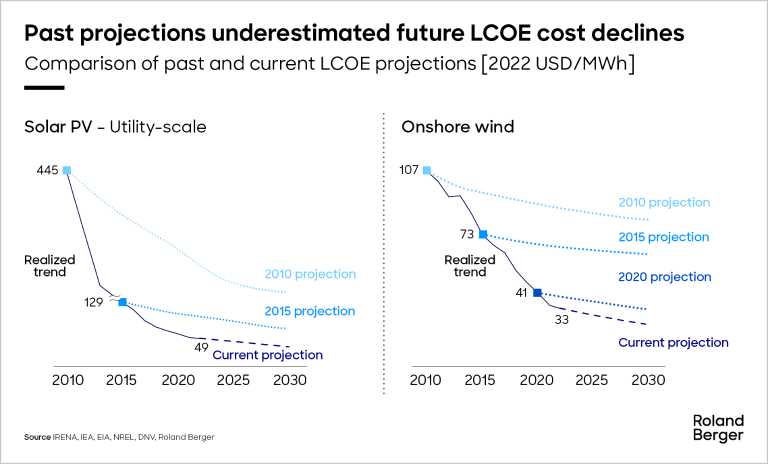

Current predictions suggest that the long-term decline in the LCOE may soon be over. But the outlook may be less gloomy than many seem to believe.

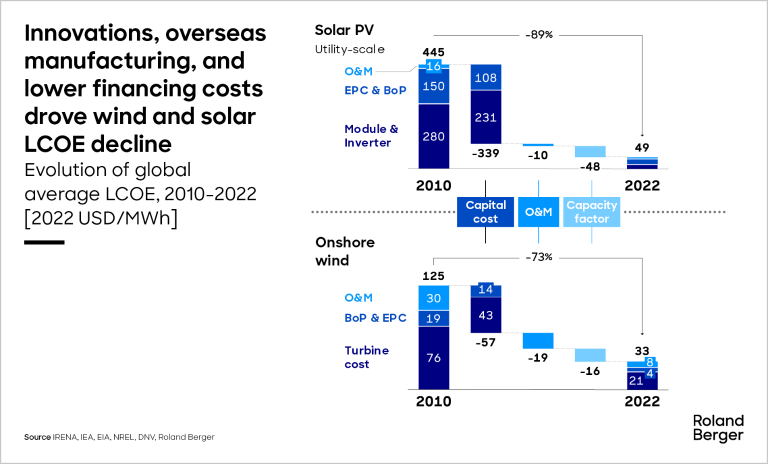

For more than a decade, the levelized cost of energy (LCOE; also referred to as the levelized cost of electricity) has been on one long downhill joyride. Per installed kilowatt, the cost of a solar is down by almost 90% since 2010, that of onshore wind by nearly 75%.

Four key factors have been the main contributors to this sustained downtrend, especially for wind and solar power:

- Sustained innovation in technology and design has combined with economies of scale to make the production and maintenance of solar panels and wind turbines more efficient and less costly. In maintenance, for example, the robotic cleaning of solar panels, data-driven preventive maintenance and the use of drones have contributed to a sizable decrease in O&M costs. Many scale benefits are largely attributable to growing experience and competition: With installed capacity for wind and solar power increasing by a factor of roughly four since 2010, the number of competing contractors and the lessons they have learned have led to more competitive bids for projects across most regions. Overall, the LCOE for renewables – incorporating initial cost, lifetime output and O&M costs – is therefore vastly lower than a decade ago.

- Financing costs, too, have fallen significantly over the past ten to twelve years. A growing inventory of successful renewable power projects has reduced perceived risk and paved the way to lower premiums on debt and the required return on equity. Even despite recent increases in interest rates, the weighted average cost of capital has decreased by around 2 to 3 percentage points since 2010.

- Manufacturing in low-cost countries is the third key factor that has driven the LCOE down. The concentration of production in China in particular has enabled manufacturers to benefit from low factor prices (capital, labor and energy), government subsidies and – probably most significantly – integration in dense, highly efficient supply chains.

- During this entire period, improved data analytics have also enabled renewable project developers to identify better sites and optimize utilization. As a result, combined with improved (and much larger/higher) project designs, the global average capacity factor for new wind installations had gained ten percentage points (to 37%) by 2022. Similarly, new solar capacity has increasingly been installed in regions with higher solar irradiance (in southern USA or Chile, for instance). This, in tandem with the growing use of tracking panels, boosted the global average capacity factor for solar PV too from 14% in 2010 to 17% in 2022.

Yet this progress now seems to be disappearing in the rear-view mirror, while prospects for further improvements appear dimmer. Why?

Hitting the wall?

After hurtling downhill for over a decade, the LCOE now appears to be slamming on the brakes (see the above chart). Not without reason, the expectation is that stiff headwinds are now blowing away many of the factors that have driven the pronounced improvements we have just discussed. Let’s look at each issue individually:

- Existing photovoltaic and wind turbine technologies appear to be approaching their efficiency frontiers. Residual PV cell efficiency gains from applying already commercialized technologies will likely come only at higher cost. Wind has relied in part on increasing project scale to capture performance and cost efficiency gains, but limits to increased size and height are looming. Onshore wind farms have plateaued at around 7.5 MW, with only marginal efficiency gains anticipated beyond this size. And offshore wind will require new hub technologies such as superconducting generators if it is to advance much beyond a top-line capacity of 20 MW. Moreover, in the near term, the industry – like most other sectors in the developed economies – will also struggle with serious labor shortages and rising labor costs, increasing the effort that more fundamental scientific and/or engineering-based breakthroughs will need to contribute to maintain the sector’s track record of steady LCOE declines.

- Recent increases in interest rates have combined with inflation to significantly and adversely impact the cost of capital for renewable projects, rendering many of them unprofitable under the terms of existing power purchase agreements, most dramatically in the case of the offshore wind sector.

- At the same time, offshore manufacturing is giving way to a new trend toward re-shoring (or at least nearshoring) – in response to governments’ local content requirements, but also reflecting global trends toward enhancing supply chain resilience in an ever more geopolitically brittle world. Here too, the cost benefits afforded by low-cost countries hitherto are likely to be reversed as global wage differentials compress, and digital technology drives the convergence of total factor productivity between regions.

- Lastly, there is a growing scarcity of high-quality sites for renewable projects. Existing wind capacity may already have virtually saturated good and accessible land resources, such that a lower capacity factor for new projects could drive up the average LCOE. Installing more efficient and higher capacity turbines on existing sites – complemented by updated analytics and, where appropriate, energy storage – may provide a temporary fillip but is unlikely to reverse the trend on its own.

Faced with such a litany of adverse developments, it is easy to understand the gloomy mood of current debate surrounding future reductions in the LCOE. So, is the party really over?

What the future holds is far from a clear-cut case

(Spoiler alert: This is not the end of the road!)

The briefest glance at the two charts above should at least give us pause for thought: Based on the industry’s track record of “future projections” about where the LCOE might reach its lower limits, we can at least claim consistency. Since at least 2010, the energy industry has repeatedly underestimated its capacity to realize further cost efficiency gains. Consequently, it has often perceived itself to be at an inflection point regarding the LCOE’s downward trajectory. The question must therefore be asked: Why should we be right this time?

Perhaps we should first ask why industry experts have routinely been so wide of the mark in the past. Three reasons: We have historically underestimated the potential of innovation to improve the economics of renewables. We have likewise misjudged the cost-cutting potential of further design optimization and advances in manufacturing efficiency. Lastly, past projections have neglected to include decreases in the cost of capital, increases in the average capacity factor and the compound effect of these changes.

Even where existing technologies are nearing the physical limits of their potential, who is to say that new technologies and/or superior manufacturing techniques cannot deliver the kind of step change that would see past cost improvements continue? From perovskite PV cells to new turbine tower designs and up-tower O&M, there is no shortage of options to choose from.

Government policies are another consideration that is not cast in stone. Shifts in policy could address interest rates, ease the cost of capital, tackle the shortage of skilled labor and even broach subjects such as domestic content requirements and trade tariffs, for example – all of which could powerfully support a sustained decline in the LCOE.

Understandably, geopolitical developments are also influencing industry expectations. And there is a tangible and inherent tension between liberal efforts to maximize economic efficiency on the one hand and the dictates of climate policy on the other. Yet here again, the last word has not been spoken. Precisely these challenges and constraints must point us not in the direction of meek surrender, but must inspire us to even greater creativity and innovation.

Necessity is still the “mother of invention”, as the saying goes. We believe that the future trajectory of the levelized cost of energy has not been signed and sealed. On the contrary, we have it in our hands – you have it in your hands – to again do what the industry has done so many times in the past: Rise to the challenge of problem-solving such that, looking back a few years from now, what appeared to be a long-term trend turned out to be nothing more than a spot of short-term turbulence.

The choice, essentially, is ours, is yours.

We welcome your comments, questions and suggestions. And we would love to sit down and talk to you about finding ways through the challenges described in this article. Get in touch with our experts!