Explore the dynamics of urban vitality and the challenges of urban decay. This article delves into key factors like demographic shifts, real estate trends, and socio-economic changes, while offering actionable strategies for policymakers to foster regeneration, preserve cultural identity, and ensure sustainable urban development.

Decentralized planning: empowering regional leadership

By Bilal Rammal

Reimagining socio-economic and spatial planning

The way nations plan and deliver development is undergoing a profound transformation. As challenges become more complex and distinct across geographies, the top-down, centrally controlled approach – long the default in many countries – is losing relevance. In its place, decentralization is emerging as a powerful organizing principle, empowering regional and local authorities to play a greater role in shaping economic, social and spatial outcomes. This is not simply a redistribution of administrative tasks; rather, it signals a rebalancing of authority, accountability and resources across different levels of government. It reflects a deeper recognition that local actors are often best positioned to understand their communities’ needs, unlock local potential and act with agility. When designed well, decentralized planning enhances responsiveness, innovation and citizen trust. But when poorly aligned, it can fragment national policy, expose capability gaps and fuel inefficiencies. We explore two critical foundations of effective decentralization: governance structures and fiscal decentralization.

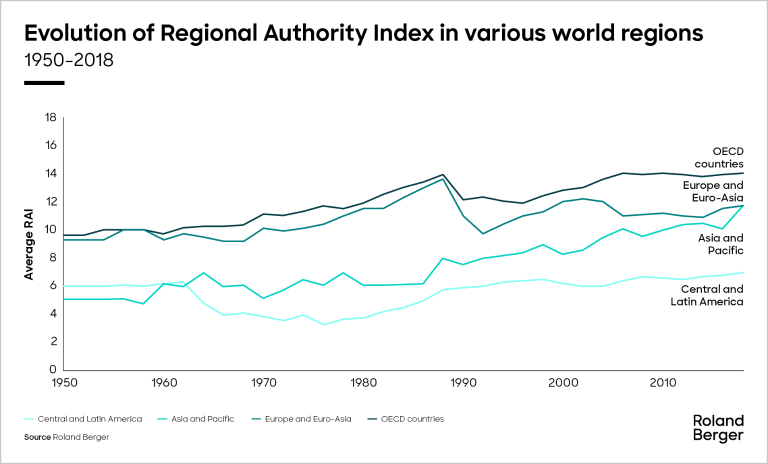

Decentralization in action – a global shift

Across the globe, decentralization is reshaping how governments manage development. From federal systems like Germany and Malaysia to unitary states like Indonesia and the United Kingdom, national governments are increasingly devolving governance responsibilities to regions and cities. The Regional Authority Index (RAI), which measures the degree of regional government power across 96 countries in Asia, Europe and the Americas (see Figure 1), confirms this trend. Between 1970 and 2018, 64 of these countries saw a net increase in regional authority, ten experienced a decline, and in 22 countries, regional authority remained unchanged.

The RAI measures the extent of power held by subnational governments across two dimensions: self-rule, which captures the authority regions exercise within their own territories, and shared rule, which reflects their role in national decision-making. Each dimension includes institutional and fiscal subcomponents – but our analysis shows that only a few account for most of the variation in RAI scores.

In the self-rule dimension, the most influential factors are:

- Policy autonomy: the breadth of policy areas under regional control

- Fiscal autonomy: the ability to raise and manage their own tax revenues

- Representation: whether regional governments are directly elected

For shared rule, the top contributors are:

- Constitutional reform power: whether regions can veto or shape national constitutional changes

- Executive control: participation in national policymaking through intergovernmental forums

- Fiscal control: influence over how national tax revenues are distributed

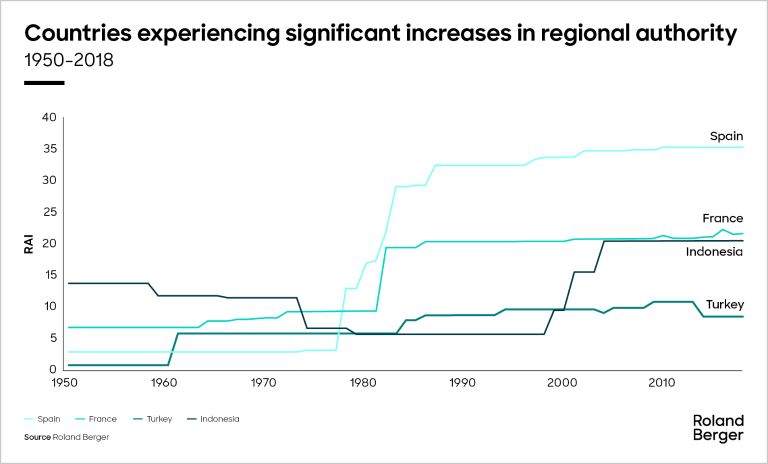

These findings confirm that regional authority is strongest where regions have real control over policymaking, are fiscally empowered and actively participate in national decision-making. This helps explain why Spain, where regions enjoy broad policy autonomy, fiscal independence, direct elections and constitutional reform power, ranks among the most decentralized countries globally (see Figure 2).

The trend towards decentralization is propelled by multiple drivers. In some cases, decentralization supports socio-political goals, such as preserving linguistic or cultural identity. In others, it is driven by economic motivations, particularly the need to boost regional competitiveness and harness place-based growth potential. Many governments also pursue regional governance to improve efficiency, clarify roles across levels of government and manage regional disparities more effectively. Accelerating urbanization strengthens the case, as centralized institutions often struggle to keep pace with the complex, rapidly evolving needs of urban populations. Closer proximity between citizens and institutions, enabled by devolved powers to local government, is considered important for more efficient matching of services to citizens.

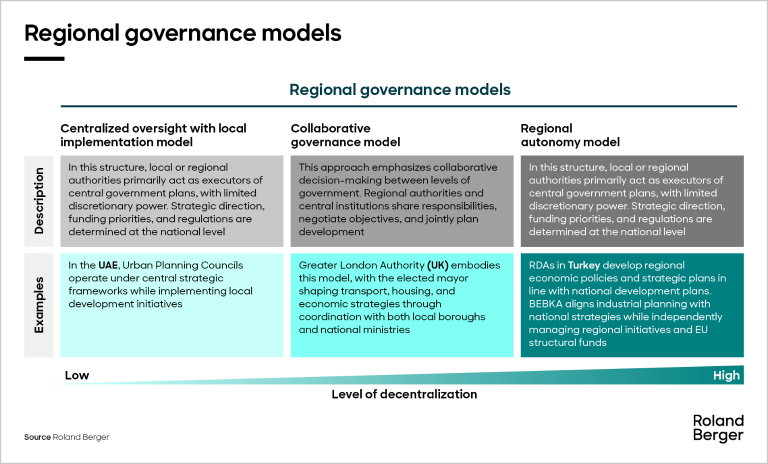

Models of decentralized governance

In response to these imperatives, governments have adopted distinct models of decentralization. These models reflect differing levels of authority and coordination between central and regional actors (Figure 3). Each model strikes a different balance between control and flexibility; regional autonomy is not always the optimal end state.

"Decentralized planning balances local innovation with alignment to national priorities."

Indonesia’s experience with regional autonomy, established by its landmark 1999 law, illustrates the risks of devolving authority without adequate institutional support. While local governments gained regulatory power, the lack of coherent oversight and coordination mechanisms led to fragmented service delivery, overlapping jurisdictional mandates and policy inconsistency, particularly in land use and permitting. The absence of horizontal alignment between neighboring jurisdictions weakened national development coherence, exacerbated regional inequalities and undermined investor confidence.

To mitigate fragmentation risks, countries have implemented a range of tools to maintain alignment between regional and national priorities. These include joint strategic planning frameworks, conditional grants tied to shared KPIs (key performance indicators), performance contracts and digital coordination platforms. Through such mechanisms, central governments can provide strategic direction while granting regional authorities the flexibility to tailor solutions to local needs.

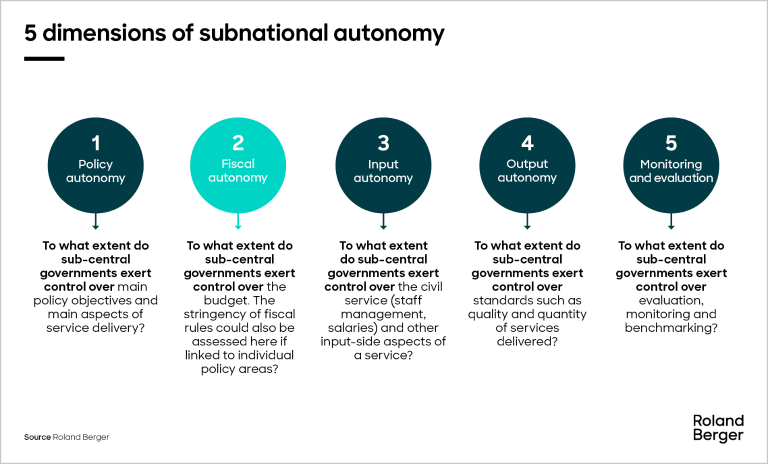

The actual degree of autonomy that local or regional governments enjoy is shaped by authority, fiscal relations and supervisory mechanisms. Drawing on the OECD framework, subnational autonomy can be understood through five key dimensions: policy autonomy, fiscal autonomy, input autonomy, output autonomy, and monitoring and evaluation (Figure 4). Among these, fiscal autonomy stands out as the most critical enabler – or constraint – of real self-governance. While legal or procedural autonomy may be granted on paper, it is actual control over resources that determines whether a regional authority can act independently or remains beholden to the center.

The fiscal frontier: empowering regions

Without meaningful financial capacity, even the most empowered regional authority remains constrained in its ability to execute. The question of who raises revenues, who allocates funds and how much budgetary discretion regions have is fundamental to whether decentralization leads to empowered governance or superficial delegation.

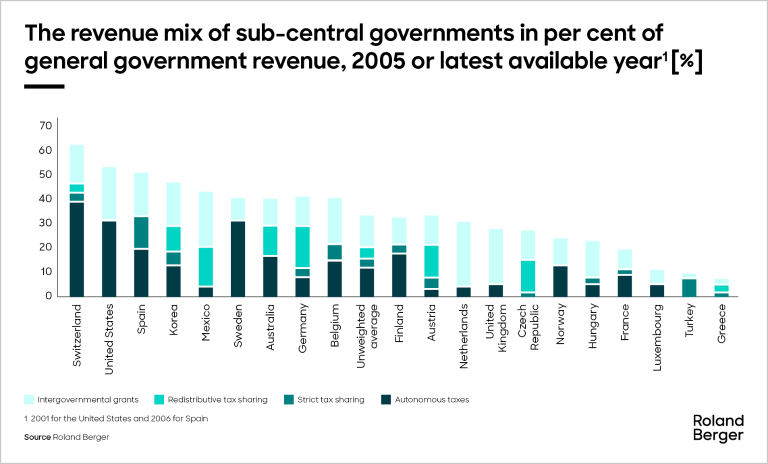

A key way to assess the depth of fiscal decentralization is to examine the extent to which subnational governments control their own revenue sources. Figure 5 illustrates the composition of sub-central government revenue across selected countries, distinguishing between autonomous taxes, tax sharing and intergovernmental grants. This breakdown reveals that while some countries grant their regions genuine fiscal authority, others maintain significant central control through transfers.

Countries such as Switzerland, the United States and Spain rely more on autonomous taxes at the subnational level, reflecting higher fiscal decentralization. Spain, in particular, has seen one of the largest shifts in regional authority, establishing autonomous communities through its 1978 Constitution. Among them, two regions – Basque Country and Navarra – distinguish themselves by collecting and managing their own taxes, paying a quota to the central government. Other countries, such as France and Greece, fund their local governments primarily through intergovernmental transfers, limiting their true fiscal autonomy and reducing their ability to invest strategically or respond flexibly to local needs. France illustrates the limits of decentralization without fiscal autonomy. Despite decades of institutional devolution, fiscal power remains centralized, with regions largely reliant on state transfers and limited discretion over taxation. This restricts their ability to pursue place-based strategies in areas like transportation and urban renewal. Without real financial levers, devolved authority struggles to translate into effective, innovative local governance.

Beyond revenue structure, expenditure control is equally crucial; decentralized regions can be significant economic actors, in charge of extensive spending responsibilities. Figure 6 compares OECD and EU countries in terms of regional spending as a percentage of both GDP (gross domestic product) and total government expenditure, highlighting the substantial disparities in actual fiscal decentralization across systems.

_image_caption_none.png?v=1483438)

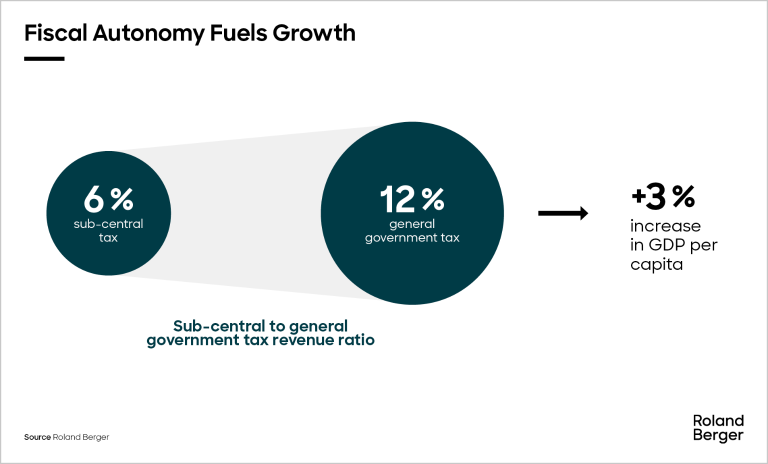

The actual fiscal capacity of regional governments varies significantly between federal and unitary systems. Countries such as Canada, Belgium and Switzerland exhibit high regional expenditure shares both as a percentage of GDP and total government spending, while many unitary countries often struggle to translate devolution into impactful fiscal autonomy. This matters for economic growth. Our analysis indicates that sub-central fiscal power – whether measured by spending or revenue shares – is positively associated with economic performance. In particular, we observe that doubling the ratio of subnational to general government tax or spending shares (for example, increasing the ratio of sub-central to general government tax revenue from six to 12 percent) is associated with a three percent increase in GDP per capita. Moreover, the data suggests that revenue decentralization yields stronger income benefits than spending decentralization, reinforcing the importance of true fiscal autonomy based on the power to raise and allocate funds independently, not just budget execution.

While some highly centralized countries might gain considerably from decentralizing, broad sub-central fiscal powers can produce diminishing returns and may also have detrimental economic effects in more decentralized countries. This highlights the importance of context-sensitive approaches to decentralization design.

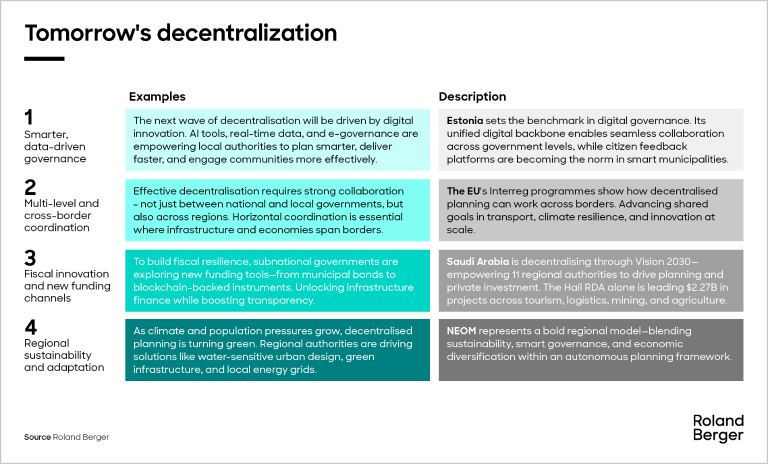

The future of decentralization: innovation and impact

As decentralization matures across the globe, its future will be shaped not just by institutional reform but by innovations in finance, technology and intergovernmental collaboration. These developments offer governments and regional development authorities new tools to enhance responsiveness, drive regional growth and build more inclusive governance systems (Figure 7). But capitalizing on these opportunities will require clear-eyed strategy, careful sequencing and a tailored approach aligned with the national context.

Conclusion

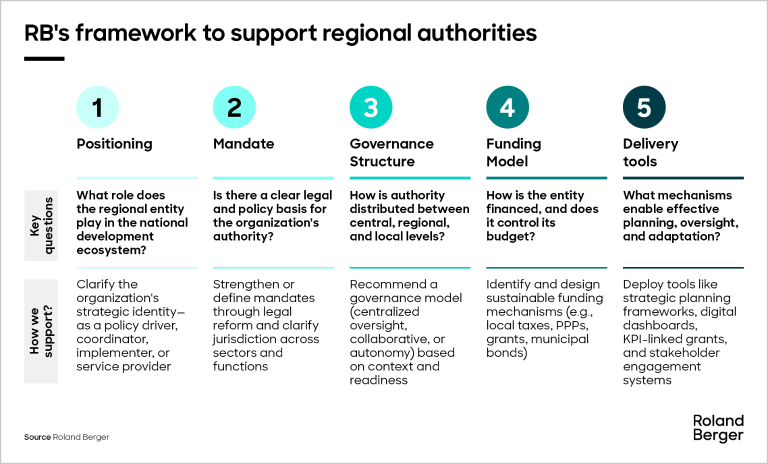

Decentralization is no longer a policy experiment, it is a defining feature of modern governance. Roland Berger can help central governments and regional authorities adopt decentralized planning models by guiding them through five critical dimensions: positioning, mandate, governance structure, funding model and delivery tools (Figure 8).

Interested in finding out more? Contact our experts to arrange a face-to-face or online meeting.

We would like to especially thank Joseph Chahwan for his exceptional contribution in writing this report.