Geopolitics 2.0

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/TA36_cover_EN_download_preview.jpg)

As organizations navigate shifting geopolitical tectonic plates, Think:Act magazine shows you how to mitigate global risks and stay on track.

Former Dunkin' Donuts CEO Robert Rosenberg opens up about how he went from a fresh business school graduate to a seasoned leader while growing his family's business into a global franchise.

Robert Rosenberg's eyes light up as he talks about one of his favorite subjects: "I love donuts! My favorite donut is the Jelly Stick," he says before breaking into technical details of how sticky buns are made. "The little puffy shells you see are yeast flavored and the honey dips. And the cake donuts are cakey, and they're leavened by baking soda," says the octogenarian speaking from his summer home in Martha's Vineyard.

The son of the founder of Dunkin' Donuts – now rebranded as Dunkin' – Rosenberg worked in the company's stores and as a district manager. His father, a first-generation entrepreneur and child of the Depression, then asked him to run the family business at the age of 25. It was a daunting task: The company was bleeding and a lot was at stake. Rosenberg engineered a fresh new strategy and a dramatic turnaround, taking the company from $10 million to $2.6 billion. But not everything was smooth during his 35-year tenure at Dunkin'. In this freewheeling interview with Think:Act, Rosenberg talks about his journey at Dunkin', his missteps and what he learned along the way.

Can you describe what you were up against when you took over Dunkin' Donuts?

Robert Rosenberg was CEO of Dunkin' between 1963 and 1998. A former board member of the International Franchise Association, his 2020 book Around the Corner to Around the World chronicles his experience building the globally recognized brand.

In 1963, within weeks of me graduating [from Harvard Business School], my father asked me to assume leadership of [Universal Food Systems, at the time a conglomerate of small food service businesses]. I came to the conclusion that the business really could stand a change in strategy: niching down to one focused business, basically. That was the first phase and it worked incredibly well. We decided to focus on a coffee and donut shop and starve the other businesses of capital and our time and begin to build that business in very focused market areas. At first, you can imagine that the management team was kind of off-put by this youngster coming in who was wet behind the ears. But as we began to achieve some success, the team started to coalesce behind me and I brought in other senior executives who were highly talented. Five years after we assumed responsibility, profits had grown with this new focus strategy from $100,000 in pre-tax profit to $800,000. The next five years were a different story. But the initial strategy was overwhelmingly successful.

As a 25-year-old without really much experience under your belt, how did you even start thinking through the challenge you saw in front of you?

I think one of the big helps to me was the ability to go to graduate school. It was clear to me that the most important function for a leader was to bring together management to fashion a strategy that provided a unique advantage. [At first], everything worked well. I was 25-30, we were now public. But a company my father couldn't sell for $1.5 million was worth, in 1968–69, something like $120 million in market cap as a public company. I began to change the strategy to look upon myself as a franchising business, rather than a focused coffee and donut shop. That's when the trouble began. Whatever humility I might have had in the early years of not knowing a lot had vanished. I got seduced by Wall Street and the need to keep my market price high. I took my eye off the core business and began to focus on what it would take to keep earnings growth upwards of 50% a year, which was naïve. Then I ran into real trouble. So I had to mature. There's an old saying: You can't put an old head on a young body. In my case, that was absolutely true. It was a result of that near failure that I began to mature.

You mentioned that others in the company saw you as someone who was wet behind the ears. How did you counter that?

I didn't come in to tell them what to do. Basically we caucused and we talked about the dilemma we were in, the tactical issues we were facing. If I were to look at my predecessor, he was spending a lot of time with the team solving and putting out fires. So the question we had before us was: How could we put the fires out by virtue of having broader policy, a different strategy? The company that I joined in 1963 was called Universal Food Systems. The team would meet and we decided that we were going to focus on one of those businesses that was in our midst. Before this, the prior management had lost confidence in a coffee and donut shop concept by itself. They were building the last 26 stores the year I joined: all restaurants that served hot dogs, hamburgers, breakfast – and they had store sizes anywhere from 18 to 90 seats. What we decided to do was focus on a 20-seat donut and coffee shop, go back to the roots of what was successful when I went off to college and we did it as a team. But that's how we coalesced, and then I ran into a few lucky breaks. We made some decisions to back up our strategy that worked out overwhelmingly well. People began to feel good about the direction we were heading and earnings were growing, bonuses were being paid.

"I had to mature. There's an old saying: You can't put an old head on a young body. In my case, that was absolutely true."

You had eight businesses in all and decided to focus on donuts and coffee. What made you believe this was the diamond in the rough?

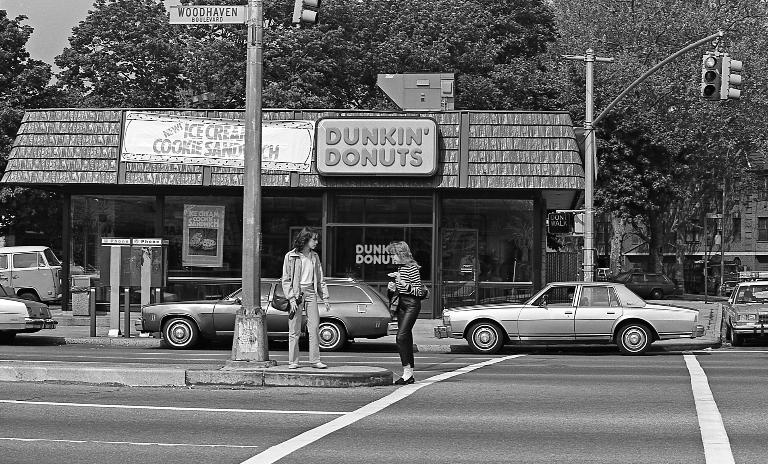

Early on, when my father and my uncle decided they needed to diversify their business, they opened a small awning store in Quincy, Massachusetts, called the Open Kettle. It was no more successful than the other 1,500 donut shops that existed in 1948 in the state of Massachusetts: It did $1,000-1,500 a week. It served superior coffee and great handmade donuts made fresh throughout the day, but it was a little awning shop where you couldn't see in it. When a competitor opened nearby, they decided to rip it down and put in a new California-style business. That store went from $1,000 a week to $5,500 at very modest prices: a dime for a cup of coffee and 55 cents for a dozen donuts.

As they began to change, they lost confidence in the ability of that narrow menu – breakfast snacks and bakery take-home products – as the basis of the business, and they began to change it. My belief was that [it was] the only thing that we really had in our portfolio of little companies that was unique, that had somewhat of a sustainable competitive advantage. Now I wasn't sure how far it could go – it did show signs it was temperamental. It was more of a bakery than it was a restaurant, or at least equally, but it was the best option I had available at the time. It made the most amount of sense. We weren't as refined as we ultimately became, but overall, more things worked well than didn't, and it was the right choice.

To what extent did you have to rethink the coffee and donuts business for the so-called "new age"?

Dramatically. We started with a 20-seat counter in a question mark style with porcelain cups. We had a separate takeout donut section and we made donuts on-premise in every single store. As time went by, drive-through windows [and self-service] became important. We did away with porcelain cups, went to paper. We eliminated the question mark counter – at some great consternation to our customers – and we changed the way we went to market as a result of some experimentation some franchise owners had done on their own. Instead of a 2,000-square-foot donut shop with 1,000 feet of retail space at high rents to manufacture donuts on-premise, we went to centralized operations that would make donuts and distribute them. We moved away from being a donut company to a beverage company. When we changed the service delivery system – paper cups, faster delivery – coffee grew from 35-40% to 60-70% of the business. We went into more commissary-like operations for production and we focused more on beverages and self-service and distributed that and took the product beyond the four walls of the store to wherever people work, shop, travel, play. The profitability and returns on that investment improved dramatically.

A lot of that was listening to franchisees. The case of distributing the product to other facilities under our name – large petroleum stations, theaters, convenience stores – was really pioneered by our Philippine franchise owners. I told them that's not the way we go to market. But they convinced me that they had a better way, and we began to adopt it in the US. It proved to be a huge change. The customer, the competition and technology is constantly changing. If you don't change your strategies, you're gonna be left behind. We, as a management team, were willing to adapt to all those changes. And we did so in a very conscious way by revisiting what we wanted to be, what we wanted to have and which four to five strategic levers we were going to pull at any given time to allow us to do that.

As CEO, how did you develop the ability to pick up signals, even if they are weak, and then translate them into something that works for the business?

Initially, I didn't do that, and that was when we ran into trouble. I went into what I can only describe as "the arrogant period." I was reading a book called The Best and the Brightest by David Halberstam. It was about the Kennedy/Johnson administration and the Vietnam War, how the government [had] some of the best and brightest Ivy League-educated people, but they weren't going into the towns and hamlets where the war was being waged: They were operating on body counts and on data. Sitting there watching some problems that were a result of my diversifying from a donut and coffee company to a franchise business and taking my eye off the business, I came to the realization that I was guilty of the very same thing myself.

So we caucused together and decided what we would do as a team: Each of us would visit at least 100 stores a year with a district manager. I personally asked [franchise owners] two questions: If you had to invest in this business again, would you do it all over again? That was my acid test of whether or not the franchise was offering returns for the effort and the risk they took. The second question was: If they were CEO, what would they do differently than I do? I wasn't there to inspect the store. I was there to listen and show concern for both the district manager as well as the owner. And slowly but surely, with that kind of mindset we started to get ideas pumped into us for products – and ultimately how we reconfigured the stores and changed our service delivery system, how we distributed our product and changed the returns at the unit level. So it was as a result of making a terrible mistake that I began to learn a new better way of listening better, and the whole management team did, and it served us well for the next 25 years.

"The best way for me to manage was to have a team of people that were, in many ways, smarter than me. I wasn't challenged by that; I was comforted by that."

You talked a bit about the mistakes you made. How did you came out of that?

Well, when leadership makes a mistake, it doesn't just affect the leader: It affects all followers. So earnings were faltering, the stock price started to fall – it fell as low as $1.70. Franchisees weren't happy. They lost confidence in management and started an $80 million class action lawsuit, which at the district level was found in their favor and could have spelled the end of the company. It was a tumultuous, sad time. One of the key guys, my classmate from business school, lost confidence in my leadership and left the company.

When I started running into trouble, I started to blame other people: my ungrateful franchisees for suing me, the guy that left me as disloyal. I began to blame everybody except the person that counted the most, which was myself. It wasn't until I read that book [by Halberstam] that I realized that the problem doesn't lie in our stores, but in ourselves. It was then that we started to come out of it. It was tough. But that's part of growing up. Life is lumpy, and then you really get paid for living through the lumps. That's when, if you're smart, you grow the most. But if you get through, you come out a lot better on the other side.

Over your 35-year stint at Dunkin', how would you describe your leadership evolution?

I basically synthesized what I thought were the four major roles or activities of a leader, [starting with] shepherding strategy: What do you want the company to be? What do you want it to have? What four to five strategic levers do you pull to achieve an objective? The second was to recruit and retain an organization that was capable of implementing that strategy. Those are the two I came to the job understanding. The third, that I came to as I matured, was the need for the CEO to communicate and align all constituents – the board, franchisees, employees – and that is a time-consuming task. Most people think that if they communicate in writing or they say it once at a company meeting, it's absorbed and picked up. Not true. It's an endless task. [Fourthly], there were maybe four or five times when certain issues spelled life or death for the business: so crisis, and the management of crisis.

I didn't come that way in 1963: It was a process evolving through trial and error, through taking courses, listening, making mistakes, looking at myself objectively. Fundamentally, I came to the conclusion that I had some strengths and some weaknesses. And the best way for me to manage was to have a team of people I could rely upon that were, in many ways, smarter than me. I wasn't challenged by that; I was comforted by that.

The management team was together for 20 years, the top 20 people. We worked well together until we got bought out in a hostile takeover, when I was forced to sell the business in order to save it. I could see clearly firsthand the impact of this terrific team of able people pulling together, many of whom had better insight about what to do than I did. I didn't have to get all the credit. I did learn this as time went on: When things go wrong, the buck stops [at the CEO]: They will take 100% of the blame. When things go right, you share the credit with everybody.

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/TA36_cover_EN_download_preview.jpg)

As organizations navigate shifting geopolitical tectonic plates, Think:Act magazine shows you how to mitigate global risks and stay on track.