The small-satellite market is booming but smallsat launches face severe bottlenecks. Europe needs to develop and secure a microlauncher solution.

Small satellites and the growing demand in microlaunchers and ridesharing

Interview with the CEO of Kineis about the different possibilities to launch small satellites

The market for small satellites is growing like never before based on a massive demand for imaging and communications across the globe. However, there is little availability of affordable launch solutions for small satellites. Microlaunchers and rideshares on heavier launchers offer a solution to this launch bottleneck. In this interview, Alexandre Tisserant, CEO at Kineis, talks about the difficulties connected to launching small satellites and shares his thoughts on the hype around investments in microlauncher projects. He also outlines Kineis' decision process behind selecting either dedicated microlaunch solutions or one of multiple ridesharing options.

How does microlaunchers’ value proposition compare with that of rideshare solutions?

Alexandre Tisserant: The choice depends primarily on the mission. Many players have launched hundreds of smallsats for earth observation missions, and this segment is well covered by rideshare solutions. You don’t strictly need microlaunchers to launch smallsats, then, but they can be very useful for some missions.

What exactly does your company need? Do you prefer dedicated microlauncher flights or rideshares on heavier launchers?

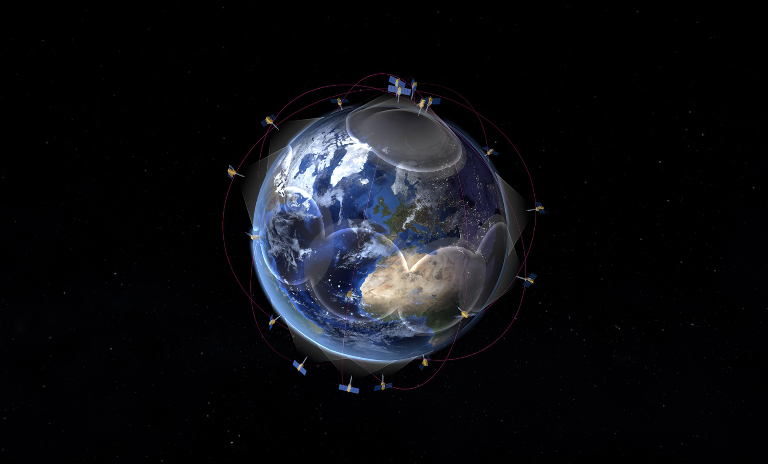

Alexandre Tisserant: Kineis plans to launch 25 nanosatellites in clusters of five for each of five different orbital planes. Five 30-kg satellites per orbit don’t even fill a light launcher like the Vega operated by Arianespace, or even a PSLV, so rideshare solutions make sense for us. However, launch slot availability has to fit our deployment schedule, and the probability of having a rideshare flight for our targeted orbits in the next six to eight months is close to zero. That is why we are considering both dedicated microlaunchers and rideshare flights. Ultimately, everything depends on launch availability, launch costs and the ability to reach our targeted orbits.

"Dedicated microlaunches are so much more flexible. You can even make last-minute adjustments to your satellite, so scheduling is far easier. But there won’t be room for all the microlauncher projects under development."

What are the advantages of a dedicated launch on a microlauncher?

Alexandre Tisserant: By definition, you share a rideshare launch with many other customers. You don't decide on the launch date or the parameters for injection into orbit. A dedicated launch on a microlauncher is much more flexible: You can even make last-minute adjustments to your satellite, so scheduling is far easier.

Does Kineis also consider the solutions offered by last-mile delivery companies such as D-Orbit and Momentus?

Alexandre Tisserant: Absolutely. These solutions support flexible orbit injection for rideshare launches. And now that players like SpaceX have brought rideshare costs down to USD 5,000 per kg, I think this type of player has something to offer satellite operators with needs like ours. Today, SpaceX and Momentus/D-Orbit offers are cheaper than microlauncher offers.

Essentially, there are four options for launching smallsats: (1) dedicated microlaunchers; (2) rideshares with the upper stage of the launcher performing the orbit rising phase; (3) rideshares with a last-mile delivery system; and (4) rideshares with the orbit rising phase managed by the satellite's own propulsion system – though we have abandoned the latter option.

Current microlaunchers are less reliable than larger launchers, but you still consider them. How come?

Alexandre Tisserant: We are willing to take a little more risk to lower the launch price and keep to our deployment schedule. As I said, five launches should deploy our constellation, and losing, say, five satellites to a launch failure would obviously be problematic. It would set our business plan back a few years. But we could still do business. Rather than having a complete network from day one, we are betting on a large number of satellites that can easily be replaced in the event of a failure.

Would you prefer a European launch solution to deploy your satellites?

Alexandre Tisserant: Given our schedule and supply side constraints, non-European launch systems are the only option we have. Limiting launcher diversity will also make our processes reproducible. In theory, we could use five different launchers, but the legal and administrative aspects of preparing for each new launch would then be more time-consuming. No more than one or two launch partners would therefore be ideal. What matters to us is not the nationality of the launcher but our deployment schedule.

Do you see microlaunchers that only service private sector demand as economically viable?

Alexandre Tisserant: I think there are far too many projects for the size of the market. Yes, smallsats launch projections indicate growth. But if you leave out SpaceX's Starlink constellation and a few others, there is not enough to feed all the microlauncher projects. I think there is a bubble. There won't be room for everyone, because the likes of SpaceX are not going to use competitors’ launch systems. So "no", I don’t think a business model relying solely on private sector demand is viable.

So, you think public contracts are essential to give these players a chance of survival?

Alexandre Tisserant: Yes. The public sector shouldn’t be the only client, but recurrent public sector demand is vital to the space business in general. France and Europe need to push harder on public demand. But I’m not talking about subsidies: Public demand means there is an industrial asset to develop. While that obviously implies a need, I am convinced that many needs of public institutions can be addressed by industrial space assets.

How do you explain the current hype around public and private investment in microlauncher projects?

Alexandre Tisserant: I don't have an explanation. But what is certain is that there will not be room for all these projects. In the US, lots of private capital, a culture open to risk and investors’ recent interest in space might explain some of the hype. And in countries where these projects are publicly funded, national interest in sovereign access to space capabilities surely explains investments in microlauncher programs. But European players have also been inspired by US dynamism: The Silicon Valley-driven tech industry inspired a generation of European entrepreneurs to develop successful projects after a few years' time lag. That said, I think Europe would never have pioneered microlaunchers, because it is not in our culture to take risks – with some exceptions, and even with public funding. D-Orbit received funding from the European Investment Bank in 2018, for example.

What is your opinion on players like SpaceX and, going forward, Amazon (Blue Origin, Kuiper), who can create their own demand for their launchers?

Alexandre Tisserant: I think they are special cases. SpaceX and Amazon have massive investment capabilities and are run by people with a long-term vision. However, uncertainty still surrounds visions such as Elon Musk’s desire for a human colony on Mars. Starlink is an ambitious project that responds to an identified global need: connectivity for all. But it is still legitimate to wonder whether that is ultimately just a way to feed demand for its own launchers.

What do you think of new launch service business models involving brokers, "digital" reservation platforms and innovative financing?

Alexandre Tisserant: Established brokers such as Spaceflight can be useful to satellite operators who need a partner to prepare missions with launch vehicle operators. At Kineis, we have a good team who can do this in-house.

Regarding launch booking platforms, a service-oriented approach will let you book a launch just like you would book a plane ticket today. Similarly, satellite industry players (like Loft Orbital) are adopting a "space-as-a-service" mindset and have value propositions focused on service and financing. Particularly in the space industry, this business model will free operators from massive early-stage capex, for example. We are seeing players start to offer innovative financing solutions with customized components backed by a banking partner. That can be attractive to customers. In my opinion, standardizing the space sector should cement this "space-as-a-service" mindset and encourage adoption of these new business models: If the interface between launcher and satellite became completely standardized tomorrow, many more organizations would be able to build and launch satellites and move toward turnkey space services linking satellites, launches and data.

How will the market for microlauncher solutions and small satellites evolve? How will the market impact your organization, and what could be the opportunities? We invite you to contact us via email or connect with Manfred Hader or Darot Dy via LinkedIn to discuss your thoughts.

Register now to receive regular insights into Aerospace & Defense topics.