AI think, therefore AI am

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/think_act_magazines_artificial_intelligence_roland_berger_cover_download_preview.jpg)

What exactly do people mean when they talk about AI in 2018? Where do I start if I want to embrace AI in my business? Get your questions answered in our Think:Act magazine on artificial intelligence.

by Janet Anderson

illustrations by Frank Höhne

Paying women less for the same work has been illegal in many countries for decades. Yet figures show that overall women still earn significantly less than men. What causes this gap? And what are companies doing to address it?

Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff told the World Economic Forum in January 2017 that every CEO today needs to look at whether they are paying men and women the same. Wage discrimination has been illegal in many countries for decades, yet the pay gap persists. According to the International Labour Organization, the global average is still somewhere around 20%. The World Economic Forum's Global Gender Gap Report 2016 shows that although progress has been made in many countries, parity will not be reached any time soon – at the current rate, it will be over a hundred years before we close the gap. Why does it matter? If the average working woman earned the same as the average working man over her lifetime, this would improve family finances, bring greater financial security to those at the lower end of the pay scale and boost children's prospects. It would also improve women's pensions, reducing the number facing poverty in old age.

There is also a benefit for employers. According to research by Glassdoor, three out of five people would not apply for a job where they believe a gender pay gap exists. Clearly, it boosts an employer's brand to demonstrate that they pay fairly. Not only that, a number of studies have shown that gender-diverse companies produce higher financial returns – diverse teams bring different points of view, reflecting the diversity of customers. Closing the gender pay gap is not just the right thing to do, it is also the smart thing to do.

Looking behind the numbers is critical. US-based recruitment consultant Korn Ferry holds data on 20 million salaries at 25,000 organizations in over 100 countries. Their analysis from 2016 revealed that while the average woman's salary in the UK was 29% lower than the average man's overall, when comparing women and men at the same level, with the same function, and in the same company, the difference was reduced to just 1%. Similar results were found in France and Germany. The gap appears to have all but vanished. How? "Today the problem is not so much unequal pay for equal work, but rather the fact that men and women are not doing the same sort of jobs, in the same companies, in the same functions," says Benjamin Frost, VP and general manager, reward products, at Korn Ferry. In short, more men than women work in high-paying sectors and more hold senior roles.

"Corporate structures were largely defined in the 1950s and 1960s... As a result, there are unintentional but subtle ways in which the playing field is tilted."

Which poses the question: What is it that leads women to lower-ranking jobs at lower-paying organizations? The answer, it seems, is simple. It starts with education. Higher-paying salaries are generally in science and technology industries, but statistics in most countries show that fewer girls study these subjects at school compared with boys, so they are not qualified for jobs in IT, engineering or R&D.

And even if women do enter these professions, they still face what Frost describes as "headwinds." "Corporate structures were largely defined in the 1950s and 1960s when the world was very different. As a result, there are unintentional but subtle ways in which the playing field is tilted to male and away from female strength," he says. He believes that companies need to be more proactive when it comes to getting staff into the talent development pipeline, rather than relying on people pushing themselves forward. Evidence shows that women are much less likely to do that. They are more likely than men to self-select out. "This creates a gap that never gets closed," he says. He also believes that there are not enough realistic role models: The myth of the superwoman is a damaging message.

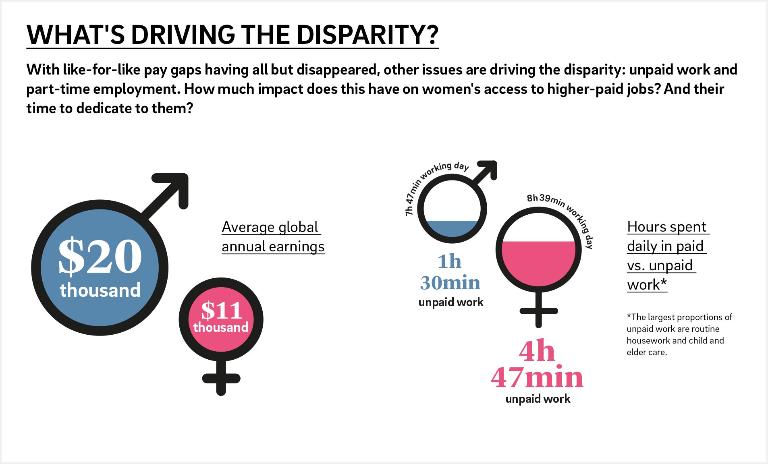

The biggest factor making a difference in a woman's earnings over her lifetime is family. And it's not just child care. Much of society's unpaid work is still carried out by women, meaning many take part-time work, and part-time work is associated with lower pay and fewer chances of career progression.

But, why should this be the case? Harvard economist Claudia Goldin believes that value in the workplace is determined to a large extent by how interchangeable an employee is. The more unique an employee's skills, the easier it is for them to command a higher salary. At the same time, it is precisely because the employee cannot easily be substituted that the job is more likely to require a fulltime commitment. If a person can only work restricted or flexible hours, they need a role where they are substitutable, and these roles often come with a lower salary for just that reason.

Perhaps the first step when it comes to addressing the gender pay gap is transparency. Publishing data is, of course, only a first step. It won't change anything on its own, but it does shine a light on the problems and enables employees, employers and the government to understand better where the biggest differences are, helping to identify where women's career progress stalls and to start making changes to address this. Goldin points out that technology and other factors also make a difference by lowering the cost of substitution, even in highly skilled work. In the US, where drugs are more standardized and computer records are centralized, it is possible for pharmacists to share roles. This leveling effect means that pay differentials are lower between women and men pharmacists and is an example of organic change within an industry leading to a better outcome in terms of the gender pay gap. But, Goldin has argued, this kind of change cannot simply be mandated across industries.

Salesforce continues to monitor its compensation after its first internal pay audit in 2015 revealed discrepancies between men and women's pay. It has now committed to auditing its payroll every year and adjusting salaries where an unjustifiable gap appears. One impact this has had is that managers of teams in which a pay discrepancy has emerged are starting to ask how they can do things differently to prevent it in the future. And the US-based outdoor clothing retailer Patagonia, for example, has combined several approaches – fully paid family medical leave, fully paid maternity leave, free on-site child care and a company culture that rewards collaboration. Over half the managers are women and 100% of new mothers return to work after maternity leave.

Many women leave work when they have their first or second baby, and most intend to return. The difficulty is finding what the US economist Sylvia Ann Hewlett has called "on-ramps" – the routes back into a career. Often women end up re-entering at a lower level and miss the career trajectories that lead to high-paying jobs. UK bank TSB is tackling just this issue with a campaign that seeks to identify women who are returning after an extended period of absence and help them with the transition.

It is not just women who we should be helping to enact change, but also men, argues Anne-Marie Slaughter, professor at Princeton and a vocal advocate of gender parity. The real revolution, she says, would be to stop seeing the home as a gendered space but rather as both a male and female domain, just as we now see the workplace.

Perhaps we are beginning to see a generational change in what employees want from work. Some studies indicate that it's not only women who are prepared to sacrifice salary for more time to do the things that are important to them. Millennials appear to want not just a work/family balance, but a work/life balance as well. If employers find they have to offer this kind of flexibility across the board, at all skill and function levels, the pay differential between part-time and full-time work might begin to disappear – and with it, the gender pay gap.

In 2017, Equileap, an organization that aims to accelerate progress toward gender equality in the workplace, ranked 3,000 companies in 23 countries. French cosmetics company L'Oréal took the top position. It earned the award by ensuring strict equality in all measurable areas – access to promotions, relocations, training and salary reviews. In France, its gender pay gap on a like-for-like basis was 3.21% for management and nonexistent for other employees in 2016. How did L'Oréal achieve this? Long-term effort. "At L'Oréal we share the strong belief that diversity in all functions and at all levels enhances creativity and innovation. But having a conviction is worth nothing without concrete actions," says Jean-Claude Le Grand, L'Oréal senior VP of talent development and chief diversity officer. It also has measures in place that ensure equal career opportunities, such as paid parental leave and flexible work.

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/think_act_magazines_artificial_intelligence_roland_berger_cover_download_preview.jpg)

What exactly do people mean when they talk about AI in 2018? Where do I start if I want to embrace AI in my business? Get your questions answered in our Think:Act magazine on artificial intelligence.

Curious about the contents of our newest Think:Act magazine? Receive your very own copy by signing up now! Subscribe here to receive our Think:Act magazine and the latest news from Roland Berger.