How crisis can fast-track business transformation

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/TA_32_001_EN_Cover_download_preview.jpg)

Think:Act Magazine explores how successful companies face the challenges of our time with creativity and agility to enter a New World.

Article by Neelima Mahajan

Illustrations by Sören Kunz

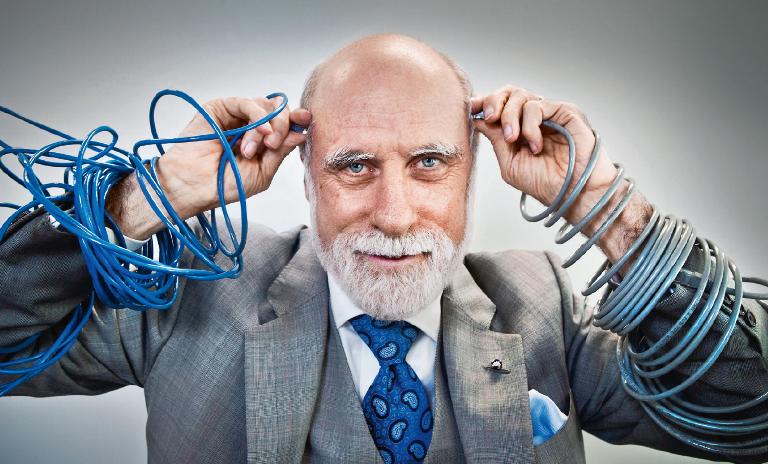

In 1973 Vinton Cerf and Robert Kahn invented TCP/IP, the communication protocols that would lay the foundations of the Internet as we know it today.

The Internet, arguably one of the most revolutionary inventions of recent times, paved the way for further applications such as email, the World Wide Web, WiFi, file-sharing and mobile communication technologies, all of which have changed our lives in immeasurable ways. Cerf and Kahn went on to win the Turing Award in 2004 for their pioneering work. Nearly five decades have gone by and as Cerf looks back at his game-changing invention, he says, "What we are doing right now [with the Internet] is what we were imagining we could do if we had enough capacity 50 few years ago." Looking at the future he sees endless possibilities: "[The internet]" is a very, very open environment," he says. "People should take advantage of that and not imagine that just because it's been around for a long time, there's no new thing to do. In fact, there's an infinite number of new things to do. Software is this endless frontier."

In this wide-ranging interview with Think:Act, Cerf talks about everything from the concentration of power in the hands of a few digital companies and the challenges in regulating the internet, to the coming digital dark ages and the internet of interplanetary space.

The recognition of today's world wasn't complete 50 years ago. The pieces of it were there. For example, very quickly after the email idea came along, people recognized the utility of being able to communicate asynchronously, then distribution lists were created. And among the distribution lists that I remember being created early on, one was called Sci-Fi Lovers: we were all engineers and geeks and we would argue over who were the best science fiction writers and what were the best science fiction stories. That was a social network. The next one that I remember was called Yum Yum, for restaurant reviews in Palo Alto. Those were clearly social phenomena.

So even though they were fairly simple in their character, they illustrated what was possible. We still use distribution lists today, we still use electronic mail, but now we use these other applications that have risen as part of the World Wide Web. We've anticipated or foreseen, or invented a lot of the tools that we use today in much more elaborate forms. The one thing that caught me by surprise was the mobile phone, the smartphone in particular, and the capability to have that much computing power, a camera, a radio and the ability to interact with the Internet all in something you put in your pocket.

The mobile phone makes the Internet more accessible, and the Internet makes the cell phone more useful because of all the content on the net and all the applications. Of course, we have millions of apps that run on smartphones today. So I would say that it wasn't a total surprise to end up where we are but I don't think we would have imagined in detail all the applications that were invented, nor I think were we anticipating the level of penetration into the private sector.

Information sharing and collaboration [on the internet] have had very positive effects, and they've been so valuable.We've also seen the same neutral platform being abused in a variety of ways. We see cyberattacks that are the result of vulnerability in software. We haven't figured out how to write software that doesn't have exploitable bugs.

Vinton Cerf was presented with the Turing Award in 2002 for his role in designing the internet's basic communication protocols. He has served as vice president and chief internet evangelist for Google since October 2005.

We have people launching [distributed] denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, generating misinformation and disinformation, people taking advantage of social networking to promote extreme content. We've discovered a variety of ways in which the internet and the web can be used for harm. It's complicated by the fact that the perpetrator could be in one country, and the victim in another. We need international agreements about how to track down, identify and apprehend people doing harmful things.

It's exactly the reason that the Secretary General of the UN proposed a High-level Panel on Digital Cooperation two years ago raising this question of how can we preserve the positive potential of the Internet and the World Wide Web while we defend against its abuses and try to minimize their harms. That's a huge challenge, it's one which can't be done purely technically.

There are some things which you can do to prevent abusive behavior on the technical axis, but we also have to have what I'll call post-talk reinforcement, where we tell people, "If you do these things, there will be consequences if we catch you." If you have a global opinion about acceptable behavior, peer pressure can be a powerful tool just like small amounts of gravity are weak but a large mass brings a large amount of gravity and keeps the planets in place as they go around the sun.

It's sometimes very hard to imagine how people might take something and do with it that which you had not expected or intended. People are enormously creative, which is exactly why the Internet is such an interesting environment: people invent new ways of using that platform, but unfortunately, some of those new ways are harmful. So the honest answer is that you can't guarantee to anticipate all of that. You need institutions that are, in some cases, global in scope and agree on practices that will inhibit or at least punish some of the harmful behaviors that emerge out of this incredibly rich and open platform.

I still think that openness is vital to its continued evolution. We have to evolve institutions and international agreements in order to protect against or defend against harmful abuse while we're trying to keep this as open as possible for all the benefits that that confers.

"We need to teach people to think critically about what they're seeing and hearing, because that's a primary filter."

There are institutions that exist not because of the internet: INTERPOL or Europol are examples. There's a global commission on the stability of cyberspace which has been proposing norms of behavior that are applicable on a global scale and their position is that if you don't yet have international agreements and treaties, you could at least have norms which are not necessarily enforceable but at least they point in the direction of what could be international agreement.

One of the first norms they proposed was that we all agree not to destroy or interfere with the basic infrastructure of the internet: so don't attack the routers, don't attack the domain name system, don't go after the optical fiber networks, the same way we don't drop bombs on schools and hospitals. We agree that as an international norm, and of course there's the Geneva Accord, that we try to adopt on a global scale. Norms are things that you can achieve, I would say at least voluntarily. And at some point, you may conclude, enough people may conclude, that a norm is so important that we should turn it into something enforceable where there are sanctions for violation. I suspect that there will be things like that emerging.

There are a few things that we could explore. For example, anonymity has turned out to be a two-edged sword. It's important for people to be able to search the Internet anonymously or to contribute to discussion anonymously because if they identify themselves, they might be at risk. On the other hand, anonymity confers a kind of a shield and people can behave very badly because they think they're anonymous. So we actually need the full spectrum of identification, ranging from anonymity all the way up to strong authentication. On that end of the axis is strong authentication.

The reason that's important is that there are some situations where you want to be assured that someone else can't pretend to be you and take actions in your name: financial transactions, real estate transactions or even political assertions. When you have strong authentication, you [can] protect yourself from being misrepresented or allow yourself to do electronic or digital transactions in cyber space in such a way that's enforceable in a court of law.

So if you and I have a contract and we digitally sign it, we use strong authentication to identify ourselves. That agreement needs to have meaning in a legal context. So there are a number of mechanisms that we can put in place that will enable some of those properties to be achievable: [such as] two-factor authentication and digital signatures using public-key cryptography.

That's a very interesting phenomenon. The Chinese have invested very heavily in the internet and they have more users than any other country in the world. Very large institutions have been created ... At the same time, the Chinese government sees criticism as harmful. From a technical viewpoint, you have to – "admire" is probably not quite the right word – but at least be impressed by how they have managed to fashion their implementation of the internet in order to manage the behavior of the population.

They've introduced social ranking and other things as a way of providing incentives for certain kinds of behaviors. I don't agree with some of that but the flexibility of the internet design permits these things to happen. We have a concept that countries have sovereignty within their borders. And so do the Chinese. Within that context, they have every right to do whatever they want in terms of implementation of the internet in their country. Now, when those behaviors leak out or when attempts are made to force those controls outside of a national border, you're starting to get into some international issues and conflict...

There are some countries that shut the internet down during elections, for example, out of the concern for misinformation and disinformation. We have to learn how to tame this beast so as to maintain its utility while suppressing some of the abuses. We can teach people to think critically about what they're seeing and hearing.

The internet itself did not come out of Silicon Valley exclusively. It has quite an international history. With regard to US and Chinese perspectives, it's a competition like every other product. What is it that people are looking for and which product will suit their preferences best? We tend to want a very open environment. The Chinese products appear to be designed in order to control the environment. You can see tensions because [of] the possible need for some more behavior control on the network in order to reduce abusive practices. It's not as if these two views are totally incompatible.

We have to find some place in between. There's also a simple cost argument, how much does the equipment and the software cost, and there will be competition among the providers of internet-based equipment. Some people say that the internet will split into the Chinese and the American parts. I am unpersuaded because I think that interoperability will turn out to be very important. Even the Chinese recognize they need to be able to interoperate with the rest of the internet for commercial reasons. Their economy needs to be able to sell products and services outside of the borders of China. I think we haven't seen the end of this story yet.

"I wouldn't be surprised if by the end of this decade that virtually anyone who wants access to the Internet can get it and can afford it, and it will be sustainable."

The cost of getting access to the internet is easily borne in countries where disposable income is high. It's harder if you are in a country where the average disposable income is less. So we have to drive cost out. The cost of the equipment needed to get access to the internet is coming down. Especially in parts of the world where the economies are still growing, you're finding a lot of people designing and building equipment that is less expensive than in the more developed countries. We need to adopt policies that will encourage investment in infrastructure so that we get more mobile phone capability out there, more Wi-Fi, more optical fiber.

In Uganda, Google and others built an optical fiber network in Kampala and then made it available as a wholesale service to retailers who then resold the wholesale access to the internet to customers and added products and services on top of that. Because everybody got the same access through the wholesale system, they could compete – consumers had a choice of different access providers. That's one way in which to stimulate competition and offer users choice. Even in the developed world, we'll find places where the internet is inadequate.

We're seeing technology stepping up to deal with that. Elon Musk's Starlink system anticipates tens of thousands of satellites in low Earth orbit around the globe providing access to the internet to every square inch of the planet. The question then will be, what will the cost be and will it be sustainable? [There's been] a startling increase in the number of undersea optical fiber cables being built. I wouldn't be surprised if by the end of this decade virtually anyone who wants access to the internet can get it and afford it.

We certainly don't think that you should have to repeat everything that the US or Europe has gone through to get to where it is today. One of the fallacies of Internet expansion discussions is that, somehow, everyone has to go through every single stage of 2G, 3G, 4G, 5G, … If you're starting in the year 2020, you might as well start with 2020 technologies. You get to jump on the train no matter where the train is on the track. That means that you don't have to have an accumulated investment. You get to start with whatever the current technology is and to be up to speed with everybody else.

"I think that people should not make the assumption that just because you appear to be at the top of the heap right now, you'll stay that way."

The biggest concern that we generally have is companies exercising some kind of monopoly power to inhibit competition – and there may not be an opportunity for new market entrants. Adopting policies that will encourage and facilitate market entry will reduce the potential hazards of the small number of large competitors. It's important to remember that companies that appear to be at the top of the heap often disappear.

I have been told by economists that it's not unusual in some markets to have three competitors. In the US, for example, we have three major car making companies. In terms of space, we're starting to see a few major competitors showing up that were capable of making rockets to get us into outer space.

Think about search. AltaVista was one of the best search engines coming out of Digital Equipment Corporation's Research Labs. Then came Yahoo, then Google, then Bing. So we're seeing a continued evolution of competition in these kinds of markets. This isn't to say ignore the problem but rather, just be aware that it's not a static environment, it's quite dynamic.

I understand the motivation, which is somehow to feel that you are not dependent on a small number of large companies. Two things to be aware of: first, the companies that are providing Cloud-based services are competing with each other. So there's choice. There's also technology which is making it possible for you to move back and forth among the various Cloud providers.

The second thing, which I think Tim's interests don't take into account, is an economy of scale. It is really quite striking when you look at data centers that make up the Cloud to see how efficient they are. The bigger they get, the more efficient it becomes because it doesn't take a huge number of people to run a significant data center, partly because it's heavily automated and partly because the people who are there might primarily be replaced by physical equipment.

It sounds democratizing and attractive, and collaborative. Suppose you have a laptop and it has some of my stuff on it, and your laptop fails, and so you'd go out and you have to buy a new one. The question is whether you're gonna go through a lot of trouble to make sure that my data gets copied along with yours into the new machine. Do you have any incentive for that? You could argue, "Well, you should do that because your data is sitting on somebody else's machine and you would want them to do what you're supposed to do to save my data." But I don't see the same incentives driving that behavior and I also don't see the economy of scale. So I am still a little unconvinced that this particular idea is actually going to manifest in the same way that I think Tim would like it to.

Writing is a very important part of our social history. The ability to communicate with the future involves being able to write something down and have it persist over a long period of time. The various media in which we have written have varying longevities. If you look at Cuneiform tablets, some of them are 5,000 years old and they are still readable if you happen to be able to read Cuneiform. Then you look at things like Vellum, for example, that's the sheepskin or goat skin, and that stuff could last a thousand years or more. Then you look at the digital technologies and you realize that maybe they don't have the same properties. Look at seven or nine-track tape. You don't know whether the oxide is going to stay on the tape or whether when you try to read it, it falls off. Or can you even find a seven-track or a nine-track tape reader? [It's the same for floppy disks, CDs and DVDs.]

Even if those media are able to hold the bits, and there is no guarantee that they will stay embedded in the media forever, even if they're still there, you may not be able to find something to read it. In order to maintain digital persistence, you have to keep copying the bits into new media so that there will still be readers available to read the bits. Then it gets worse, because even if you can read the bits, you don't necessarily know what they mean unless you actually have a software available that can correctly interpret the bits.

But this software has to run on a computer, and so now what? What if the software was designed to run in a particular operating system, on a particular piece of hardware? A hundred years from now, the hardware doesn't exist, the operating system isn't in use, and so the software that you thought would be useful for interpreting the bits doesn't run anywhere anymore. So the bits are worthless at that point.

This is a very serious problem. To the extent that we invest more and more in digital content and its creation and use, that investment tells us how devastating it would be if that information simply goes away, because we don't know how to interpret the bits. I am a big fan right now looking at building systems [that] retain, maintain and sustain digital content over long periods of time, including our ability to correctly interpret it. If we don't do that, the 22nd century won't have a clue about what the 21st century was all about because we are increasingly using digital media to record our history and that history will evaporate if we don't think about it.

We are going to experience what are call the emergent properties from some of these inventions that we're making. Machine learning, for instance, and neural networks have transformed our use of AI compared to what it looked like 50 years ago. But we've also discovered that those same machine learning technologies are brittle in the sense that you train them to do something and they do that very well within the space that they were trained but then when they encounter something that was not part of the training set, sometimes they just break in an unanticipated and sometimes, catastrophic way.

One thing I can say is that, we are far away, at the moment, from being able to do what human beings can do and so we should be cautious about the scary-robots-are-taking-over kind of scenarios because I don't think we're anywhere close to that. We are at risk with regard to algorithms that we rely on to help make decisions because we should be worried about an algorithm which has bias or brittleness built into it. If we don't recognize where it has become brittle, we may actually either make a decision or be influenced to make a decision that's bad.

What human beings can do and what machine learning has not been able to do is take a small sample of experiences and then extrapolate and generalize from that. I don't think that we have software that's capable of doing quite the same thing. We have software that can find correlations in masses of information. We're far away from emulating what humans are capable of doing from inferring and generalizing from small numbers of samples.

I hope we get to the point where we can rely on AI to help us do that, because we might accelerate our ability to understand the world and how it works. But I see all of these as augmenting tools. I still think that's its primary value as opposed to taking over the world or having us turn over too much responsibility to AI.

The purpose behind this was to provide a richer networking and communication environment for both manned and robotic space exploration, and we demonstrated the capacity and utility of this already. As early as 2004, prototype software was literally transmitted to Mars and updates were placed on the rovers and the orbiters in order to store and forward networking to pull data back from Mars, from the rovers, that had landed there, of which, there have been quite a number now.

The most recent versions of the protocols had been standardized, they're on the International Space Station, we anticipate that they'll be used in the American Artemis program, the return to the moon, and they're freely available, that's open source. The interplanetary system is a nascent operation at this point and freely available to all spacefaring countries, and my hope is that we will propagate this interplanetary network mission by mission over the succeeding decades of this century so that by the end of this century, we will have a very rich networking capability to support manned and robotic space exploration.

Some people say, "Are you building this so the the aliens come and talk to us?" No, we're building it for our own equipment, our own both robotic systems and potentially manned missions to take advantage of a richer communication environment.

![{[downloads[language].preview]}](https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_image/TA_32_001_EN_Cover_download_preview.jpg)

Think:Act Magazine explores how successful companies face the challenges of our time with creativity and agility to enter a New World.